Centre Block Rehabilitation Project: Reno of the Century

This article first appeared in the March 2021 issue of the Heritage Ottawa Newsletter.

By Carolyn Quinn

The Centre Block rehabilitation project is being called the “renovation of the century.” Years in planning with a decade-long schedule in place, the massive-scale $665 million fixer-upper aims to bring the building into the 21st century by blending heritage conservation with modernization.

Rob Wright, Assistant Deputy Minister with Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC) who is heading up the project, hosted an eye-popping group tour of the site last December. Wright described the recent restorations of the West Block, the Government Conference Centre (now the Senate of Canada Building) and the former Bank of Montreal Building on Wellington Street as “training for the heritage Olympics.” Centre Block is the main event.

Designed by visionary architect John A. Pearson, the Neo-Gothic, Beaux-Arts style building replaced the original Centre Block that burned to the ground in 1916. Assisted by gifted craftsmen such as sculptor Cléophas Soucy, his brother wood carver Elzéar and ironwork master Paul Beau, Pearson oversaw every detail of the building’s construction.

Phil White, Canada’s Dominion Sculptor, describes the resulting structure as “one of the most distinctive government buildings in the world because there’s nothing formulaic about it. Each artisan left his personal stamp on it.”

Pearson’s sculpture program intentionally left hundreds of stone blocks uncarved so they could be sculpted over the years to portray Canadian history as it evolves. Phil White is Canada’s fifth Dominion Sculptor.

It is this national treasure that must be carefully protected during a complex rehabilitation project based on two main strategies: sustainability and universal accessibility. Extensive contemporary interventions include seismic upgrading and asbestos removal, overhauling mechanical and electrical systems, and restoring some 22,000 heritage elements, half on site and half carefully removed and restored elsewhere.

Work is well underway. The first phase of the project begun in 2019 focuses on excavation, demolition and abatement work. Some 5,000 truckloads of bedrock have already been excavated from the front terrace area stretching the length of the building. A new four-level underground and fully accessible Visitor Welcome Centre is under construction. It will be the first new building on Parliament Hill in more than 100 years.

The sweeping sandstone retaining wall and grand stairs, designed in the 1870s by renowned American architect Calvert Vaux, that form an integral part of the heritage landscape had to be dismantled. In order to reinstate these features precisely, each stone was numbered and catalogued before being removed to storage. Concerns about the infringement of the Visitor Welcome Centre on the landscape were taken to heart by the architects who have designed a sensitive option that minimizes impacts on the lawn and heritage features. An entrance is tucked on each side of the stairs with gentle sloping ramps that lead off the central walkway.

Inside the building, the upper floors have been stripped down to bare bricks and iron beams. Some 2.5 million kilograms of asbestos-containing material has been taken out. Where conservators have removed thousands of moveable heritage assets, each item has been surveyed, scanned, restored and stored, some offsite, others in specially designed cases within the building. Features such as wainscotting are protected under fire-rated hoarding material. Floors are similarly covered.

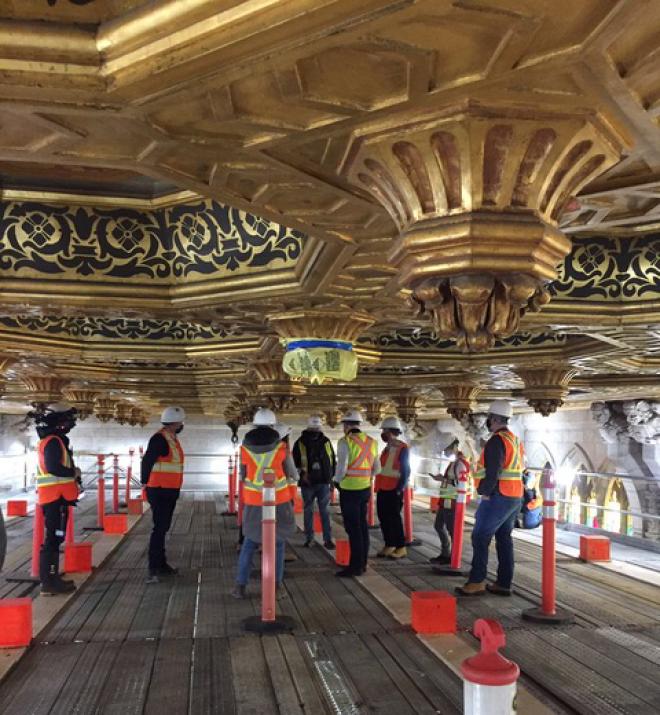

Climbing the scaffolding into the upper reaches of the House of Commons, Senate Chamber, and the Confederation Hall Rotunda was nothing short of awe-inspiring. Ornate sculptures and carvings were at eye level. The Senate Chamber’s stunning hand-stencilled suspended plaster ceiling hovered over our heads. It is to be restored on site while the intricately painted linen-covered ceiling in the House of Commons is removed and carefully rolled for restoration elsewhere.

As well as solving complicated conservation challenges, the Centre Block project is attempting to turn the most iconic heritage building in the country into a modern functioning facility as seamlessly as possible.

“All the recognizable heritage elements will be there,” says Rob Wright. “But it’s going to operate as a modern facility—carbon-neutral, universally accessible, better acoustics, speech privacy, with a digital backbone.”

That’s a tall order. It will require critical decisions that will have an impact on how the building functions for the next hundred years.

Decision-Making Challenges

With MPs moved into temporary quarters in the West Block in 2018 and the Centre Block project well underway behind boarding, questions began to emerge about the lack of transparency. How are decisions being made without cost estimates and why is the public being kept in the dark?

One of the challenges has been coordinating the number of players involved. PSPC is leading the project, but it also involves Treasury Board, the NCC, the Library of Parliament, Parliamentary Protective Services, the Commons, the Senate, and CENTRUS, the joint venture partnership providing all engineering and design management services (WSP Canada, HOK Architects, Architecture49, and DFS architecture & design).

Some design options and associated costs were finalized last year and presented to the Long Term Vision Plan (LTVP) Working Group, a sub-committee of the House’s Board of Internal Economy. The Board approved the LTVP’s recommendation to proceed with the smaller Visitor Welcome Centre option at a cost saving of over $100 million. This decision was also supported by an Independent Design Review Panel made up of professionals from across the country assembled by the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada to provide feedback and help refine schematic designs.

Similarly, after reviewing plans and costs to changes inside the Centre Block last December, the LTVP recommended and received Board approval of the expansion of the government and opposition lobbies vertically across two floors and into parts of an adjacent courtyard; the reduction of seating capacity in the galleries from 553 to 296 to meet national building code requirements for accessibility; the enclosure of the west courtyard with a glass ceiling providing public access to galleries while improving the building’s energy performance; the restoration of the glass light-well above the House of Commons Foyer, closed off decades ago; and the addition of three floors above the Hall of Honour.

Member of Parliament Bruce Stanton, chair of the LTVP Working Group, is committed to keeping parliamentarians abreast of what’s going on. Last November the group reviewed several means by which MPs could become more involved and informed on the pace of work and where their direct input could be sought before interior formats and designs are finalized. The group will soon be meeting with its counterpart, which is being constituted on the Senate side.

PSPC is doing more to bring the project into the public realm with an informative website offering details and progress updates with images and videos, and by inviting the media to tour the site and report on the work.

Still, it is a massive breathtaking project and the federal government should be shedding more light on it. A bureaucratic predilection for confidentiality is unlikely to open the project up to the public in a more comprehensive way. That impetus will have to come from Bruce Stanton and his Working Group and other MPs. It is a wonderful opportunity to invite Canadians into their Parliament, the home of our democracy, to share the splendours within it and how the building is evolving for future generations.

Carolyn Quinn is a member of the Heritage Ottawa board and Vice-Chair of the City’s Built Heritage Sub-Committee.