An entrepreneurial widow: The story behind Magee House

OTTAWA CITIZEN, By Joanne Laucius

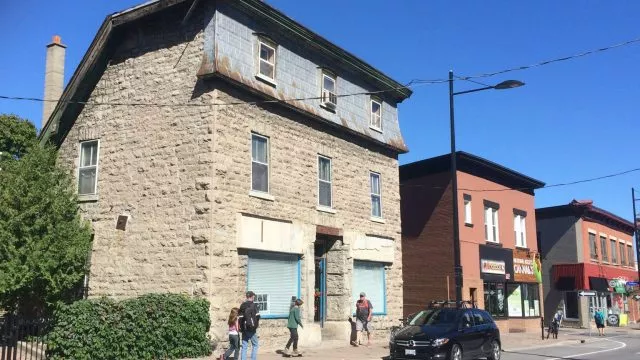

More than 130 years after the death of Frances Magee, the stone house on Wellington Street still retains the name of an energetic Irish widow who became a shrewd real estate speculator.

The west wall of Magee House collapsed Tuesday evening. Heritage buffs say the building is one of the last reminders of the beginnings of Hintonburg.

“That’s Hintonburg, not these 10-storey condos,” historian Dave Allston said. “The stonework is incredible. Now that it’s exposed, you can appreciate how they stacked those stones.”

Frances Magee came to Canada in the 1830s with her husband, Charles, who became a farmer and tavern owner. She was widowed in 1846 and left to raise three daughters and four sons who ranged in age from infant to 15. She kept on running the farm and the tavern, and was still living in a log house in 1851.

In 1871, she bought seven acres fronting on the north side of Richmond Road, running on either side of what is now Stirling Avenue north to Scott Street, and later subdivided it into lots, said Linda Hoad, a member of the Hintonburg Community Association [and Heritage Ottawa's Board of Directors] who researched the house’s history in support of its heritage designation.

Allston, who writes a blog called The Kitchissippi Museum, said Magee laid out a small subdivision in 1873. Almost immediately, she sold the southern block of the west side of Stirling Avenue from Armstrong Street to Wellington Street to an Ottawa butcher named Richard Woodland for $1,100.

The Magee House was partially built as early as April 1874. The original house had a pitched roof. The mansard roof now on the house was added about 25 years later.

Land registry records indicate that Woodland was in the house in 1875. He took out a second mortgage on the property in early 1875, likely to cover construction costs. He defaulted in 1878. In the transaction, we catch a glimpse of the shrewd Mrs. Magee, said Allston. The default triggered a clause in which she could sell the property at auction. The auction winner was her son-in-law, James Clarke, who flipped the property back to his mother-in-law for the price he had paid.

One of Magee’s sons, Charles, became a prominent Ottawa banker. Frances Magee also appears to have had a strong entrepreneurial streak. She loaned money secured by mortgages, including two loans to Joseph Hinton, whose name is still attached to Hintonburg, said Hoad.

Magee moved into the house in 1879 but only lived there for a short time, said Allston. The house was enlarged and the stone exterior was added, and its assessed value quadrupled by April 1880.

Late that year, Magee was living near Britannia on the farm of her sons James and Robert. She died in 1883, with “exhaustion” given as the cause of death. Reportedly, there were 150 vehicles in the funeral procession.

Magee’s daughter, Mary Jane Johnston, inherited the house, but died a year later. The house was rented to the Rochesters, a well-known lumbering family, for most of the 1880s. The Johnston heirs sold the property to Aaron Carruthers, a lumber shipper and member of the first Hintonburg village council, who lived there until he sold the property to Thomas A. Stott, Jr. Tenants occupied the house for the next decade.

In 1907, the house became a branch of the Northern Crown Bank, which later became the Royal Bank, and the tin-clad mansard roof was installed and the front windows enlarged. There have been reports that there is still a bank vault in the basement of the building, said Hoad.

The Royal Bank opened a new location across the street in 1941. Magee House had tenants during the Second World War era, then became the headquarters for a catering service, a menswear store and a hardware store. There was a used car dealership at the rear of the building for a brief time. Later, cab companies used the space at the back, said Allston.

Magee’s last will and testament saw her considerable assets divided among her children and grandchchildren, although her banker son Charles got nothing, said Hoad. The bequests included leaving her piano and parlour furniture to her granddaughters, along with some money for their education.

In her research, Hoad found that all of Magee’s documents were signed with an X.

“She was probably illiterate.”

Magee House was designated under Part IV of the Ontario Heritage Act in 1996 for its rarity as a stone building, the connection to Frances Magee and its architecture, said Hoad. It was cited for its “Second Empire detailing, in particular, the mansard roof with its dormers and emphatic cornice, is unique in the neighbourhood and serves to add the landmark status of the structure.”

Allston sees the collapse of its western wall as an example of “demolition by neglect.”

He has long admired the building. “It’s a cliché to say they don’t build them like they used to, but in this case it’s true,” Allston said. “When I was a teenager, I would dream that I would live there someday.”